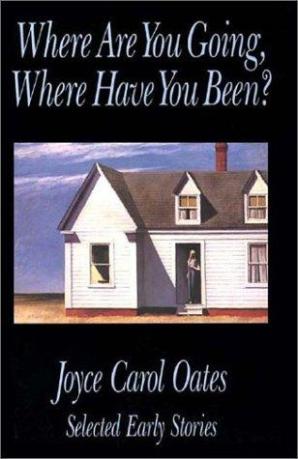

So I may be late to Women’s History Month (it’s March, in case you’re behind too), but it is indeed a month for celebrating women everywhere. In an effort to celebrate a woman I think is pretty damn rad, I’m focusing on a short story by Joyce Carol Oates entitled “Where Are You Going, Where Have you Been?” As I’ve mentioned earlier, I’m up to my ears in schoolwork, so a short story/short profile will have to do for now. If you haven’t entered the bizarre, creepy world of Oates before, here’s a good place to start. I may not have a ton of time to blog, but hey, who couldn’t use a good read by a rad writer?

Quick Read: Yes

Difficulty: Not very. Definitely an easy read.

Synopsis: Connie is just your average mid-twentieth century teenage girl–she’s pretty, fixated on her own hair, and thinks her mother and sister are just jealous of her good looks. But Connie is bored, and feels stagnant. So when a well-coiffed stranger named Arnold Friend pulls up to her house while she’s home alone telling her he’ll take her away, he’s in love with her, and he’ll take her away so that they may start their life together. While Connie thinks it sounds like a wonderful, spontaneous plan, until she begins to see Arnold’s real side, and when she does, it may very well be too late.

What makes this (short) story awesome?: Joyce Carol Oates knows how to write a brutal horror story where no blood is shed, but the violence is clearly just beyond the last sentence. Her carefully constructed story starts innocently enough, but the reader knows almost immediately that Connie is doomed. Somehow, someway, Connie is destined for tragedy, and the way Oates goes about conveying that is nothing short of breathtaking.

Oates is a prolific writer, but this short story is certainly one of her best, even if it is one of her earliest published works. It’s short, sweet, and powerful–all the things a short story ought to be. Just one reason why it’s read in many college courses–it’s a nearly perfect piece of short fiction, and a great example of Oates’ dark prose.

Some fun facts about Oates:

- Oates has written over 50 novels and dozens of short stories, short story collections, and essays. She is quite possibly one of the most prolific writers of the late twentieth century, and honestly, it makes me just want to write write write and never ever stop just to hope I can maybe publish a fraction of what she did. Maybe (probably not).

- Her books are extremely violent and so graphic that Oates addressed reader’s and critics concerns in a New York Times article entitled “Why Do You Write So Violent?” saying that those who asked this question did not realize its sexist implications. She claimed to be tired of being labelled merely as “women’s literature” and that no male author would be asked that question. What do you guys think? Does she have a point?

- Oates still teaches at Princeton, but used to live in Detroit, and many of her stories take place in both Michigan and New Jersey. Talk about your depressing American landscape settings.